“Father, you have no idea what’s going on in a factory”

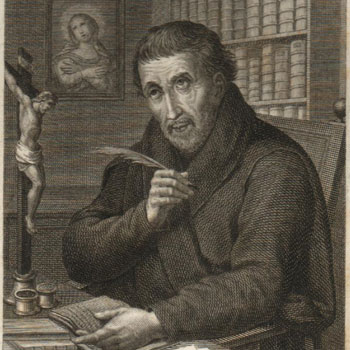

Kim Tae-jin, SJ - Jesuit Mission in Cambodia

[From “Jesuits 2022 - The

Society of Jesus in the world”]

The incarnation experience of a Jesuit working anonymously in a factory alongside exploited workers.

I met SreyTot on a Saturday in early 2016. She was a garment worker in TuolPongro industrial complex. “In our factory we can’t go to restroom whenever we want to.” She added, “We get fired if we don’t work overtime.” I responded angrily. “What? They can’t do that. It’s a violation of human rights! Go report to the union.” Closing her eyes tight, she turned her head and retorted, “Father, you have no idea what’s going on in a factory.”

For many years, I used to visit TuolPongro

industrial complex every weekend. I was getting closer to Cambodian laborers’

life, I thought. But SreyTot made me realize that I had been living in a safe

castle such as church, a university, and the Society of Jesus. So I could not

see the workers as they were.

In the second week of the Spiritual Exercises, the Son looks down upon the world and insists on descending there. Now I think I got a glimpse of why. The only way for him to deeply understand, sympathize, and save human beings was undoubtedly Incarnation: to work and live in the same place and in the same way as human beings do.

I heard the whisper of Holy Spirit inviting me to be with factory workers, but I was afraid. Not because of harsh working conditions. Labor protest in 2014 turned into a bloodshed after the government used military force, resulting in five deaths and tens of injuries. The government has been keeping a watchful eye on labor groups since then, especially on the foreigners who approached laborers.

In October 2018, I got a job at a factory.

Nobody except the factory manager knew that I was a Catholic priest. During the

first four months, I worked in a warehouse. When 13 meters high containers

arrived, we would open the back door, unload large rolls of fabric, carrying

each roll on the shoulder. Later, I was assigned to a packing department where

I put the final products into plastic bags, then into boxes, and moved them

into a container.

Sewing machine operators were often forced to work 11 to 12 hours a day in order to fill the quota. They had to risk their job if they wanted to take sick-leave or take kids to hospital. Customarily, each line was given two restroom tickets. More than two persons cannot go to a restroom at the same time in order to keep the workflow going. The line-manager’s coercive attitude made it difficult for them to exercise their legal rights to take sick leave or paid monthly holidays.

Labor workers were like fruit flies caught in a

spider web. Poor, rural families send their kids to cities to make money. They

lie about their age to work in a factory. Out of $250 they earn working

overtime, they send $200 home. With this, their parents manage to pay off their

debt, feed and educate the younger children. Three to four workers share a $30

room and eat three meals from food carts every day. They leave behind home and

family, miss educational opportunity, live a life bound to a sewing machine,

spend their youth to get old, only to barely improve their and their family’s

lives. Watching them in a factory, I realized what was essential for them:

literacy, hygiene, health, and stable income.

In January 2020, I quit the factory to open a night school, RUOM (together), offering literacy classes. Laborers come at 6 pm after 10 hours of work; we eat, laugh together, and study Khmer alphabet.

Recently I resumed teaching East Asian philosophy at Royal University of Phnom Penh. My wish is that the student workers would continue to meet and pursue their activities on their own.

Jesus’ Incarnation includes betrayal and

suffering. So does mine. I thought spending time together with laborers had

made me close to them, but I was a stranger after all. I have lived in Cambodia

and spoken their language longer than they have, yet I could not be one of

them.

As

in Jesus’s Incarnation, death comes at the end, dying of the former self.

Through incarnation as a factory worker, my body was born anew. Syrigmus and

insomnia that had been killing me for years were gone and replaced by shoulder

pain and itchy skin, probably due to heavy fabric rolls and toxic environments.

I

could not see before why they could not go to restroom, why they had to work

overtime, why they got sick so often, why they drank beer, why they sang

karaoke at the top of their voice after work, why they wore heavy makeup and

revealing clothes, why they could not read and write, why they could not save

money… On the other side of the wall, there was a spider web. Now my eye sees

it. It became visible when I set foot on the same ground as they stood on and

looked at them face-to-face, sweating the same sweat.