And they planted trees…

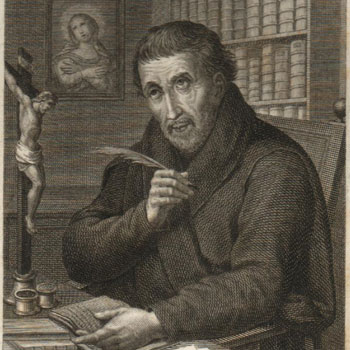

Gonçalo Machado, SJ; Jean-Pierre Sonnet, SJ - Collegio

Bellarmino, Rome

[From “Jesuits 2023 - The Society of Jesus in the world”]

On the rooftops of Rome at the Collegio Bellarmino, two Jesuits have created a hanging garden, continuing a tradition of particular significance for the Society, especially at a time when planting trees has become more important than ever.

In every age, Jesuits have created gardens. Is

that a surprise? Anyone who makes progress in the spiritual life, or who helps

others to experience God, will be quick to understand why: the garden is the

place of encounter. That is true in the Bible from the garden of Eden in the

first pages, to the city-garden of the heavenly Jerusalem in the last, by way,

in the middle, of “the locked garden” in the Song of Songs. Christ’s

Resurrection takes place in a garden and there he still awaits us. In the

Society’s history, a love of gardens has taken many different forms, scientific

as much as spiritual or else palpably manual – with our hands literally in the

soil. The encyclical, Laudato Si’ and

the Apostolic Preference, “Taking

care of our common home”, established during the last General Congregation,

lend this tradition a new relevance.

Jesuit botanists and gardeners

It was said of Solomon that “He spoke of trees, from the cedar that is in Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of the wall.” (1 K 4:33). The Jesuits have done likewise: the Society’s history is littered with botanists. Without the slightest doubt, the pioneer was Giovanni Battista Ferrari (c. 1584-1655), the first person to provide a scientific description of the citrus family. The Society’s missionary boom became evident through its enthusiasm for the plant kingdom overseas: the attention lavished upon souls was mirrored by care for the soil, and all kinds of plants, starting with medicinal species. The number of botanical gardens grew. The one created by the Portuguese Jesuit, João de Loureiro (c.1715-1791), in Vietnam contains more than 1,000 different species of plants. And Jesuit brothers have played an extraordinary role in this adventure. We cannot fail to mention brother Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1791), a highly talented artist involved in creating a garden in the imperial palaces of Peking. Another genius, brother Justin Gillet (1866-1943), created what later became the largest botanical garden in central Africa at Kisantu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Today, it is listed as a World Heritage site.

Jesuits such as Giovanni Battista Ferrari and Henry Hawkins (1577-1646) also produced aesthetic reflections on gardens. Louis Richeôme (1544-1625) was inspired by the garden of the novitiate at Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome. In his description of the garden, Richeôme draws out the Ad amorem contemplation of the Spiritual Exercises which invites us to “see how God dwells in creatures” especially “in the plants, causing growth...” (SpEx 235)

A 360 degree garden

Today, the Sant’ Andrea garden has been transformed

into an urban park, retaining its plentiful cedar trees and the large camphor

tree planted by the Jesuits. Less than a kilometre away, a new, hanging garden

has been planted on the vast balcony of the Collegio

Bellarmino.

Initially, plans were drawn up for the garden that considered the whole area from every angle, mapping out places for socialising, and secluded nooks for contemplation. An irrigation system was installed so that the garden could accommodate about 30 trees, chiefly species from the Mediterranean basin: holm oaks, pine trees, fig trees, pomegranate trees, every kind of citrus tree and a dozen olive trees. A large number of plants grow alongside them, including two enormous camellias, whose name comes from the Czech Jesuit botanist and missionary to the Philippines, Georges Joseph Kamel (1661-1706).

The centre of Rome is almost entirely occupied by stone and cement, with hardly any green spaces. By garlanding the College roof with greenery, we sought to respond to the urgency of our age. For as the botanist Stefano Mancuso has said, “Our cities, where 50 per cent of the world’s population live, are also the places on the planet responsible for the production of the largest amount of CO2. They should be totally covered in plants. Not just in designated green spaces: parks, gardens, flowerbeds and so on, but rooftops, balconies, terraces, pavements, chimneys, traffic lights etc. There should be just one simple rule: wherever it is possible for a plant to live, there must be one.”

The Bellarmino garden is a completely open

space, offering 360 degree views. An inscription in the garden quotes one of

the first Jesuits, Jerónimo Nadal. He said, “The world is our home.” From the

trees on the balcony, a tremendous sense of solidarity unites us to Jesuits and

their friends across the world who have committed to replantation and

reforestation projects to ensure that the world remains a “common home” for the

whole human family.