Learning to promote justice in a Chinese environment

To live a faith that promotes justice also means to operate and make decisions amidst difficult and challenging environments. When confronted with such environments, a variety of images will fill our feelings, imagination, minds, and hearts. Ignatian spirituality pays special attention to the discernment of images, when we are still searching for meaning as a previous condition before looking for solid solutions to concrete problems.

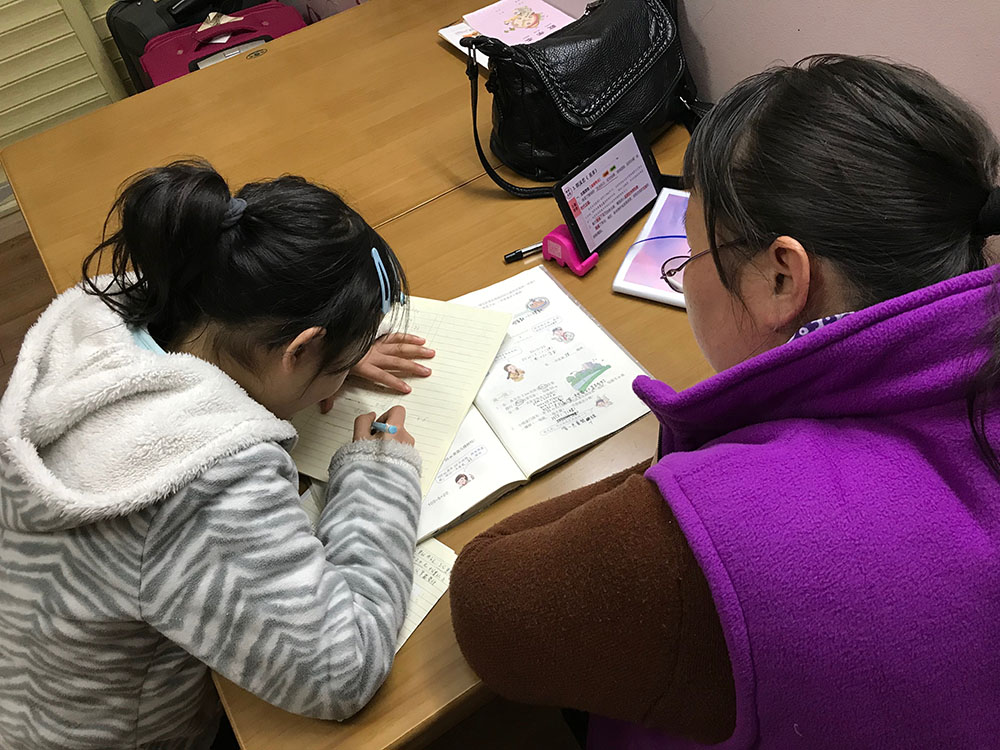

In these lines I would like to share reflections about three images with roots both in the Ignatian tradition and the Chinese culture. They express my personal learning and integration of those Ignatian elements that have influenced the way I carry out our mission in China. These images and learnings are expressed in three Chinese characters: to learn to dialogue with the different, represented by the character “Ren” (仁), which means “humanity;” to learn to hope for the improbable, represented by the character “Wang” (望), which means “hope;” and to learn how to become useless by building a sense of being “together for mission,” represented by the character “Dao” (道), which means “the Way.”

Since the time of Matteo Ricci Jesuits have been

attracted to the character Ren 仁, which represents a person

with a number two. What makes us human is the relationship with the other.

Modern Confucianists express this as the capacity to feel with another person’s

heart. The bigger the gap between these two persons, the stronger this

experience of becoming human. In my 13 years in China serving in Ricci Social

Services, I have been blessed to be in close relationship with people who were

very different from me. Leprosy-affected persons, children and adults living

with HIV/AIDS, the Chinese sisters serving them, sex workers, government

officials, etc. After all these years, it is impossible for me to understand

myself without them. They have become part of who I am and how I understand our

mission, which is the source of our Jesuit identity. Many of them, including

government officials, have become my friends, my mission companions, and my

best teachers. To dialogue with our differences has meant a long process of

understanding what unites us, what complements us, and what pushes us in

opposite directions. This dialogue has meant the construction of a space of

mutual freedom that has transformed and deepened our identities. Dialogue –

especially with those who seem to be against us – is deep inside our Jesuit

DNA. It is not merely a way of negotiating with challenging contexts in order

to achieve our mission. Dialogue has been and is in itself a fundamental part

of our mission of reconciliation and justice, as expressed in General

Congregation 36.

But dialogue does not work that fast in China, so I had to start “to learn to hope for the improbable.” When we started our service to people affected by leprosy in China 30 years ago, conditions were terrible. Even the leprosy patients could not understand why the sisters who work with us wanted to come to the most desolated places in China to stay and live with them. “When are you going to leave?” was the common question they asked of those heroic sisters in those days. The same happened when we started to serve HIV/AIDS patients 15 years ago, or women at risk five years ago. The Chinese character for hope depicts a scholar looking at the moon but standing firmly on the ground. For me, this has meant to love the present and its circumstances and to hope for the future, to serve and to dialogue every day with the present reality, knowing that by doing so we were preparing ourselves for the gift of the future. Hope has been one of the most important words in our recent congregations and one of the biggest gifts I have received in my mission in China.

This brought us to my third character: to learn how to become useless. Lao Tse wrote that the best rulers are those whom the people hardly know exist. “The best ruler stays in the background, and his voice is rarely heard.” When he accomplishes his tasks the people declare: “We did it by ourselves.” A core element in our Jesuit way of proceeding is the building of an apostolic body for the mission. The mission which does not belong to us – is not entrusted to individuals, but to the whole apostolic body. The Jesuit way here coincides with the Chinese way, or Dao (道), “the Way of the Sage King.” This is very important when mutual trust needs to be built in a Chinese context where everything changes very fast. Ricci Social Services’ 30 years of service in China is evidence that it is the continuity of a whole community and not of individual persons that makes a mission progress.

To learn to dialogue with the different, to hope for the improbable, and to become

useless. I am still far away from graduation. As we say in China, the longer

you live, the more you have to learn.

[Article from "Jesuits - The Society of Jesus in the world - 2020", by Fernando Azpiroz SJ]