Conversion in (and of) the history of the Society of Jesus

Let others write your history

By Robert Danieluk, SJ - ARSI (Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu)

[From "Jesuits 2021 - The Society of Jesus in the world"]

Conversion, understood as a radical change of life, is part of the history of the Society of Jesus, not only since its origins but even before the Society’s foundation. Think of the life of St. Ignatius of Loyola, and it is easy to see that the Society was born out of his personal conversion.

Even after the Society’s canonical recognition, some events of particular note frequently obliged the Jesuits to have a conversion, i.e, to change a facet of their lives or behaviour and be in some fashion transformed, in order to respond fittingly to the call of the Lord. Consider, for instance, the great missionary openness of those sons of St. Ignatius who, on encountering the ancient, sophisticated cultures of the East, decided to adopt a new strategy for mission in Asia, based on dialogue with local culture, instead of imposing a European version of Christianity.

Other examples could be mentioned, although

strictly speaking, a history of the conversion of the Society of Jesus probably

does not exist. This article does not aim to redress the gap, but rather to

invite reflection on what we might call “the conversion of the history of the

Society.” In fact, one of the major changes of the past, both remote and

recent, concerns exactly how the history of the Society has been told.

In the beginning, the Jesuits themselves handled the subject. From the Society’s earliest years, there were always people aware of the importance of the events leading up to its foundation. In the prologue of the Autobiography (Ignatius of Loyola, Personal Writings, ed. Joseph Munitiz and Philip Endean, Penguin Classics, 1996, 3-7) there is evidence that Fathers Jerónimo Nadal, Juan de Polanco, and Luis Gonçalves da Câmara were persistent in trying to persuade St. Ignatius to tell his complete life story. If, according to Jerónimo Nadal, “this meant truly to found the Society,” it was because of the impact his story would have on future generations of Jesuits.

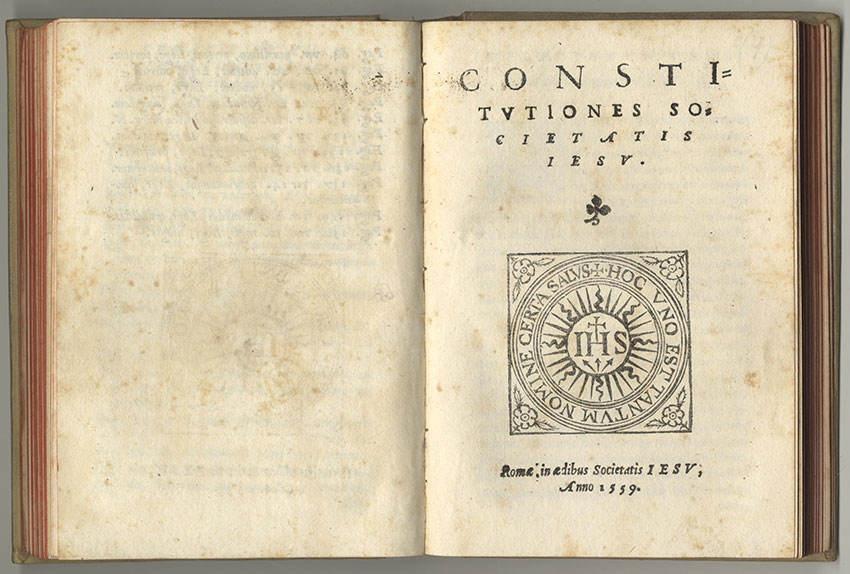

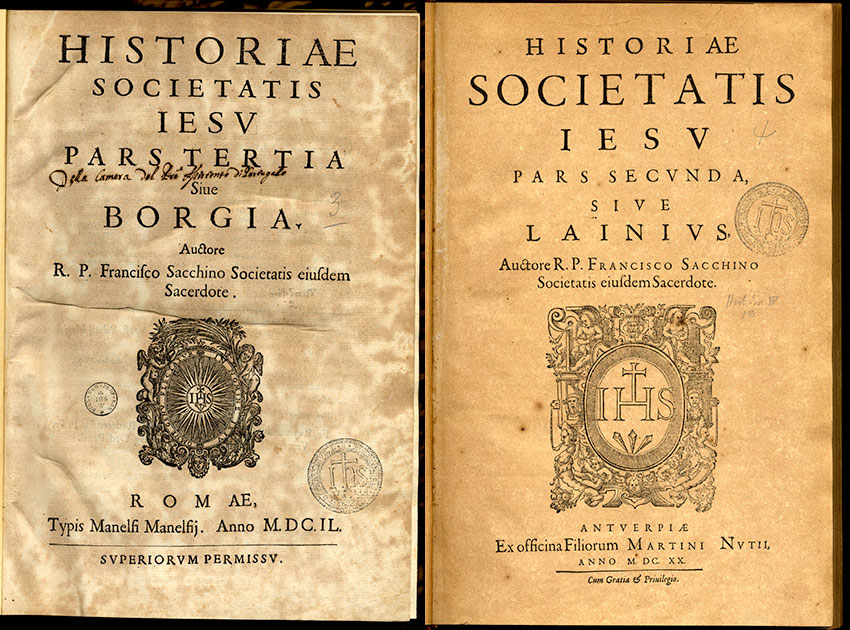

Other chroniclers and witnesses of the Society’s initial years and decades, including Polanco, Pedro de Ribadeneira, and Gianpietro Maffei, continued to investigate this history through their writing. Finally, at the start of the XVII century, a monumental history of the Society, entitled Historia Societatis Iesu, saw the light of day. Published in eight volumes between 1615 and 1859, it was the work of the official historians of the Society, all of whom were Jesuits. They narrated the early vicissitudes of the Society from its origins until 1633.

During the 19th century, one of the

“conversions” of the Jesuits’ historiographic endeavours took place. By the end

of the century, it had become obvious that the way history was written had

changed. It was impossible to continue writing the series in Latin, as had been

done at the start, more than 200 years earlier. Therefore, the Superior

General, Luis Martín, promoted a long, systematic investigation of historical

sources, with the aim of producing a history of each Province, Assistancy, or

geographical area where the Society was present, written in modern languages

and in accordance with prevailing methodology.

Just as in earlier centuries, one of the aims of this historiography was the formation of Jesuits themselves. Their history was to be read aloud, as indeed happened, in their refectories, a fact that led Fr. Martín to observe that a historian could achieve more for the formation of Jesuits than he could himself as the General of the Society, because while historians’ work is read over the course of many years, a General only occasionally writes everyone a circular letter.

The Jesuits’ history, together with the news from their most remote mission territories, proved a marvellous channel for making themselves known among their benefactors, friends, and the students of their schools, the source of many missionary vocations, as well as within the Society itself.

Another significant aspect of this history was defending the Society from the attacks and criticisms of its adversaries. As these had existed from the Society’s beginning, it was understandable that the Jesuits should defend themselves with the very weapons used to attack them: the pen and the printing press.

The Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu.

But what has conversion to do with all this? And what does it involve? The following three observations will try to answer this question.

First of all, for several decades, matters related to the Society of Jesus have sparked a great interest, and even appear to be in fashion, among many scholars. There is no lack of writers within the Society itself, of course, but these are now a minority.

Second, as these non-Jesuit scholars publish a great deal, the bibliography of the history of the Society is visibly increasing.

This number of publications presents quite a challenge for interested parties, who must navigate their way through hundreds of books and articles written in several languages. Several joint projects and particular collaborative ventures supply the proof of a true “methodological conversion.” As their numbers diminish, Jesuits should begin to collaborate more effectively among themselves and also with others.

Third, and most important, the focus of most of

this historiography has changed. With a few exceptions, it is no longer about

defending or attacking the Society: What interests the majority of scholars

today is improving the study of their subjects (whose variety is highly

surprising!) by drawing on Jesuit sources. For its part, the Society is trying

to keep the doors of its archives and libraries open, taking to heart the words

of Pope Francis, who, on 4 March 2019, while announcing the opening of the

Vatican’s Apostolic Archives for the period of Pius XII’s pontificate, said,

“The Church is not afraid of history but, rather, she loves it, and would like

to love it more and better, as God loves it!”