The story of a crazy idea

Nikolaas Sintobin, SJ - European Low

Countries Region

[From “Jesuits 2022 - The Society of Jesus in the world”]

The spiritual reality television show that has proved a hit in a secular context.

Peter was covered head to foot in tattoos: not the usual look for an R.E. teacher. And at a very young age, he had ended up in a gang. Then, several years ago, he had watched a Dutch television reality show I had been part of. That series turned Peter’s life round. Although then well into his 30’s, he resumed his secondary school studies, since completing them was a requirement for studying... theology.

There was nothing normal about the series. It

was a religious or, to be more accurate, an Ignatian reality television show.

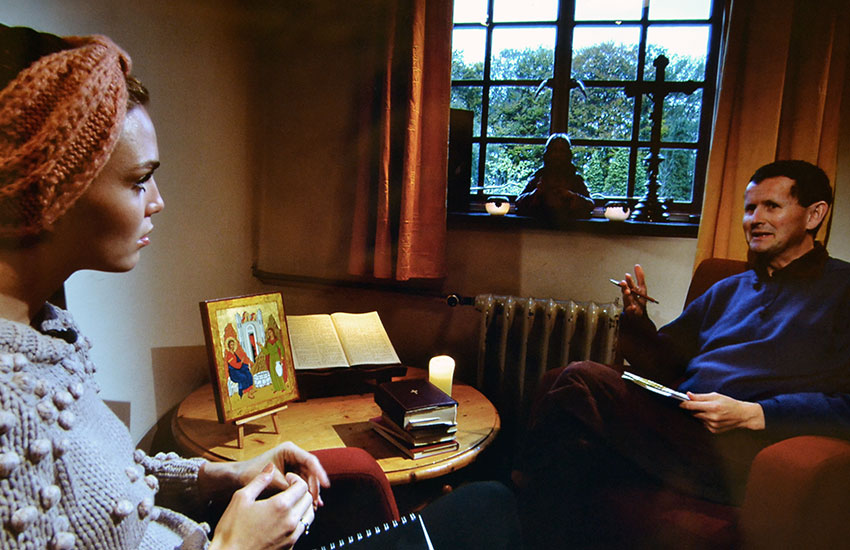

In 2013, after some soul searching, I and two other Jesuits and two women who

are experienced spiritual directors had taken up the challenge of giving the

Spiritual Exercises in an abbey to celebrities from the Low Countries.

Everything proceeded as normal: the retreatants being in silence and isolation

and receiving individual accompaniment. But 30 television professionals were

also present, discreetly filming everything, including the spiritual

accompaniment sessions. The upshot was a fascinating, five-programme series: it

was funny, rather lovely, but, above all, had striking spiritual depth. The

series was broadcast at peak viewing hours on Dutch state television. A second

series followed a year later. Each time, during the weeks of broadcast,

thousands of people took part in an Ignatian retreat offered simultaneously on

the channel’s digital platform.

Over the course of the following years, I have been delighted to hear numerous testimonies like Peter’s. The impact of this programme was, and still is, significant. It was instigated by a Dutch evangelical television channel that wanted to familiarise its viewers with Ignatian Biblical prayer. It chose the unusual format of a reality television show because this allowed it to reach a larger and non-denominational public, and in particular the fans of celebrities. Their gamble paid off. During the weeks of broadcast, many radio and TV reports covered the programme, which was also discussed in the Netherlands’ main newspapers and magazines. What is the explanation for this?

The main reason reveals a great deal about the

spirit of our age. The evangelical channel displayed astonishing pastoral

boldness in isolating stars from the world of showbiz, fashion, or sport during

seven days and nights spent in total silence. And this for a programme whose

substance was the polar opposite of their normal lifestyles. What’s more, the

channel dared to entrust one of its flagship shows to the Jesuits, a group with

whom Protestants have not always had the best of friendships in past centuries.

That takes some doing. The second reason was that the result was of undeniably

high quality. The experiences and testimonies of the celebrities were very

compelling for the simple reason that, to their amazement, they had experienced

a genuine spiritual journey. That didn’t escape notice. Lastly, but by no means

least, the programme came up at a time when Dutch Protestants were increasingly

hungry for spirituality. Ignatian spirituality seemed to fit the bill rather well.

That was 10 years ago now. For me, that experience marked a personal turning point in my life as a Jesuit. I was able to see for myself the value of creativity and apostolic audacity. In our fast-changing post-modern culture, it is both possible and desirable to innovate and to venture out on paths previously unexplored. To my surprise, the digital world and the media in general have become my main area of activity. Within a broader perspective, I think that this experience has also led to a change for the apostolate in its current form in our region (the European Low Countries, including Flanders). The digital apostolate has become the area in which our small group of Jesuits is most invested. Companions of all generations work together with a team of professionals. We also rely on the regular involvement of dozens of volunteers in the Ignatian family.

It is striking to observe just how much a strong

ecumenical interaction has developed from this presence in the online world. We

don’t hide our Catholic identity. Yet in the Low Countries above all, we are

reaching more Protestants than Catholics. The internet, after all, has no

walls. The chairman of the board of our spirituality centre in Amsterdam is

Protestant, as is the young journalist who works for our team full-time. For

both, an experience of the Spiritual Exercises was the key to their committing

to work with us. Our teams of spiritual directors are equally ecumenical. Some

of our digital retreats are given by Protestant pastors. Without denying our

differences, we are making a conscious effort to gather together Christians of

different denominations. Long-standing prejudices are giving way to

rapprochement through an encounter with the Lord made possible by the Spiritual

Exercises. And this applies to those who have been Christians “forever,” just

as much as to newcomers like Peter.