Sad anniversary: the Pontifical Suppression of the Society of Jesus

Wenceslao Soto Artuñedo, SJ (ARSI)

21 July 2023 marks the 250th anniversary of the pontifical suppression of the Society of Jesus, the culmination of a Via Crucis of persecutions in the 18th century that fulfilled a prophecy of uncertain origin: In the first century they will flourish, in the second they will reign and in the third they will perish.

The dominant political culture, enlightened despotism enhanced by royalism, was strongly opposed by the Jesuits, a very active and influential order socially and politically, although not enough to avoid disaster. It was highly esteemed, but it also had powerful enemies. In addition to the complex external causes, there were personal shortcomings and institutional grievances against the Society itself, a picture that was magnified by the widespread image of the Jesuits as overbearing and self-sufficient.

The beginning of the end was the treaty of Madrid or of Limits (1750), by which Spain and Portugal exchanged occupied zones in South America with the opposite side, and exposed the natives to the possibility of slavery since a group of seven Guarani missions passed to Portugal. The Jesuits opposed the provisions of the treaty, and, from 1755 on, they were imprisoned and deported to Portugal, from where many of them were expelled, others imprisoned. Finally, in 1759, they were accused of plotting a failed attempt against the king. The Prime Minister, the future Marquis of Pombal, began a campaign to discredit the Jesuits in Europe with half-truths, lies, exaggerations and manipulations that, after being repeated, became credible, (according to the later principle of the Nazi minister Goebbels), and fed the “black legend.”

Commemorative medal. On the reverse: Jesus and Saint Peter expel the Jesuits from the Church.

In France, after the economic bankruptcy of the irregular businesses of Father Lavalette, procurator of the missions of Martinique, the Jesuits were suppressed between 1762 and 1764.

In Spain, a false reason of State was officially put

forward, namely the participation in the riots against the minister Esquilache

in 1766. On 2 April 1767, Charles III, for “urgent, just and necessary

reasons, which I reserve in my Royal mind...”, condemned the Jesuits to the

very serious penalty of extrañamiento (loss of nationality), which entailed

the expulsion from all the King’s territories and the confiscation of their

goods. More than 5,000 religious were expelled. The Americans began to arrive

in September 1767 in Spain, from where they were sent to the Papal States. The

114 Jesuits from the Philippines arrived by two routes, until 1770.

About thirty missionaries from the most remote places, Sinaloa and Sonora (Mexico) and another group from Chiloé (Chile) received a singular treatment, since they were detained, perhaps because they were considered spies for foreign powers. Some were reclaimed by their European sovereigns, but the Spaniards remained as hostages of Charles III, imprisoned in convents scattered throughout Spain.

In Italy, the expulsion from the kingdom of the Two

Sicilies was decreed in November 1767; from Parma, in February 1768; from the

island of Malta, on 22 April.

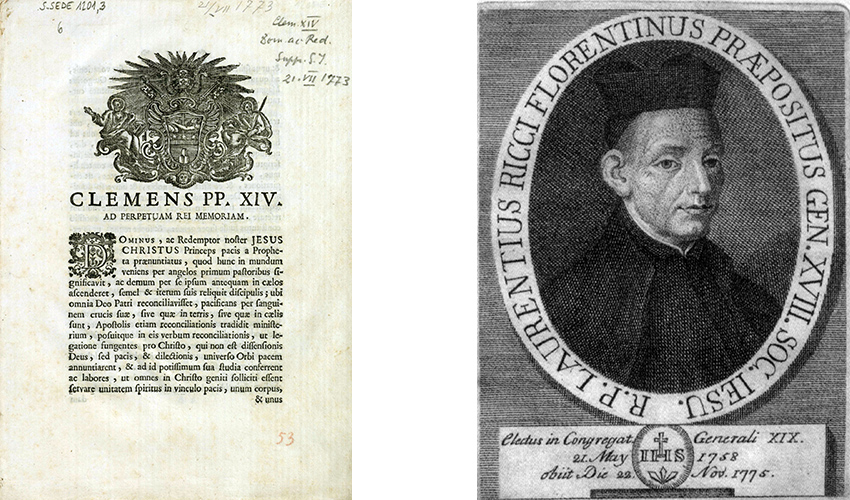

Brief Dominus ac Redemptor by Pope Clement XIV, suppressing the Society of Jesus - Lorenzo Ricci, General of the Society of Jesus at the time of its suppression.

On the death of Pope Clement XIII, Clement XIV was elected, a pope “made for the Spaniards” according to the Spanish ambassador. His successor, José Moñino, arrived in Rome in 1772 with the mission to secure the suppression of the Order, with a policy of harassment of the pope and his entourage. Thus, on 21 July 1773, the pontiff signed the brief Dominus ac Redemptor where, after listing all the suppressed religious orders, among them the Templars and the Jesuates, and referring to the charges against the Society, without passing judgment on them, declared: we suppress and extinguish the aforementioned Society, we abolish and annul each and every one of its offices, ministries, and employments, Houses [...]. [...] nor can the present Letters be challenged, invalidated, or revoked. There had been nearly 23,000 Jesuits. Earlier, an estimated 855 Spanish Jesuits had requested to leave the Society.

The brief was announced to the houses in Rome and Father

General Lorenzo Ricci, along with his counselors, was detained first in the

English College and then in Castel Sant’Angelo, in the noblest part of the

prison, but in solitary confinement. The councilors were released, but he died

after confessing his innocence, on 24 November 1775. He was buried secretly in

the Gesù.

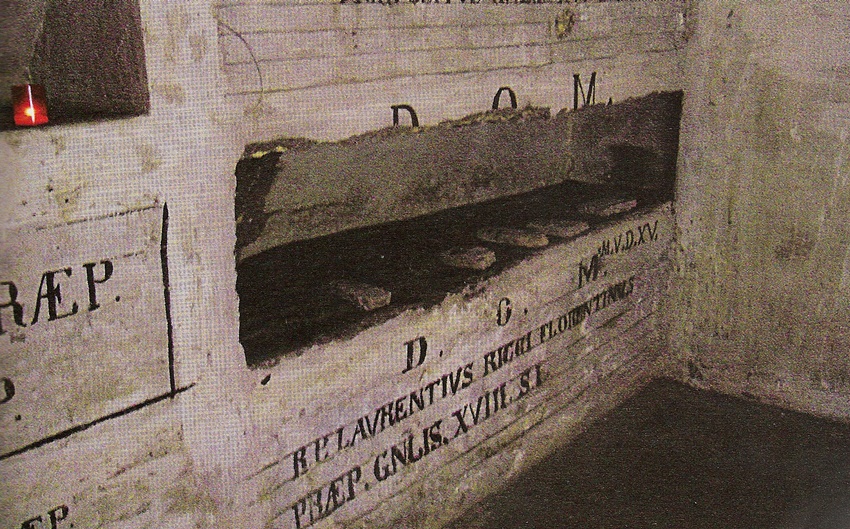

Tomb of Superior General Lorenzo Ricci in the Church of the Gesù, Rome.

The former Jesuits were offered the possibility of moving to other religious orders, but most of them remained secular priests, without community life and without Jesuit cassock. They felt themselves victims of a persecution against the Church and sublimated it by identifying themselves with Jesus in his passion, deluding themselves with alleged prophecies about the end of their calamities. They could not easily participate in priestly ministries and dedicated themselves to the promotion of culture, research and literature. Some of the Spanish coadjutor brothers and students were ordained priests, and 136 others married, having 429 children between them.

The Society was suppressed, but not extinguished. For

the Society of Jesus - harassed by the kings who held the titles of Catholic

(Spanish), Most Faithful (Portuguese) and Most Christian (French) - was

protected by a Protestant sovereign and an Orthodox tsarina, both of them with

private lives of dubious reputation and sharing the same royalist absolutism as

the others. Frederick II yielded to the pressures of Charles III by suppressing

the Society in Silesia in 1776 and in East Prussia in 1780, but Catherine stood

by her decision. Curiously, there were no Jesuits in Russia before 1772, but in

1772 Russia annexed White Russia or Belarus, where 201 Jesuits worked. They

were sheltered there long enough, until six years after the restoration, when

Tsar Alexander I expelled them in 1820.

Catherine II of Russia

Many former Jesuits joined the Society in Russia, and after 1801, some of them spread to England, the United States, Switzerland and Holland, where the brief of suppression had not been clearly promulgated either.

From these ashes, like the Ave Phoenix, when

times and people changed, the Society was reborn. It was Pope Pius VII who had

recognized its survival in Russia, partially restored the Society in the Two

Sicilies, and universalized it by the bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum

of 7 August 1814. In Italy there remained little more than 500 elderly Jesuits.