“No one should ever make us despair!”

By Mathias Moosbrugger - Collegium Canisianum, Innsbruck, Austria

[From "Jesuits 2022 - The Society of Jesus in the world"]

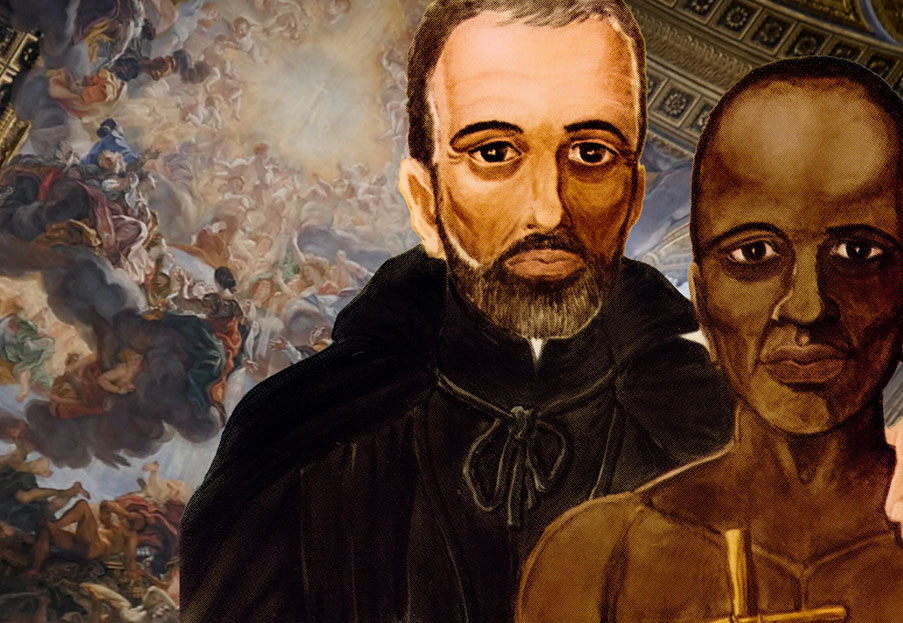

Peter Canisius and the Jesuit vision of the world

The closing years of the 1550s were not particularly pleasant for the Jesuits. Not only did they have to contend with the death of Ignatius in July 1556, but the previous year Paul IV, a declared enemy of the Jesuits, had been elected Pope. He sought to take immediate advantage of the Jesuits having no leader by turning the Society into an order in line with his ideas. To this end, he dissolved the first Jesuit assembly to elect a new Superior General and banned all Jesuits from leaving Rome. He resorted to subterfuge to ensure that elections for the next Superior General could not be held until 1558. At the time, no one knew what his real intentions were and whether ultimately, he was planning to strike the Order a death blow. What was nonetheless perfectly clear was that the future of the young Society of Jesus hung by a thread: no one could have predicted Paul IV’s death a year later. In fact, in 1558, practically anything seemed more likely than the Jesuits having a long-term future in the Church.

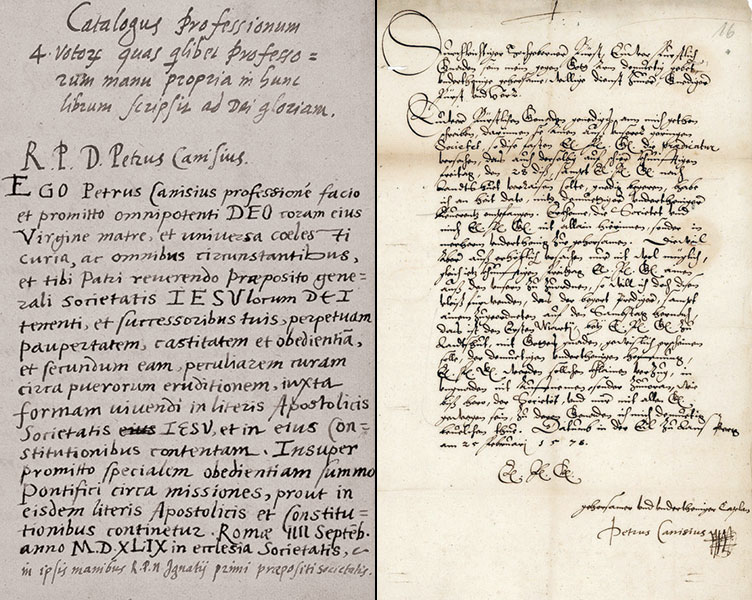

Peter Canisius found himself in Rome right at the heart of affairs when matters took a dramatic turn for the worse. Just weeks before his death, Ignatius had named Peter the first Provincial of the Province of Upper Germany. In this role, he had attended the thwarted election for the Superior General in 1556, and the subsequent, successful election in 1558. Straight after the election of Diego Laínez, Peter was sent on papal orders on a diplomatic mission to Poland with the nuncio Camillus Mentuati. And so he transitioned straight from penury in Rome to poverty in Poland.

Previously, Paul IV had made his life impossible

(alongside that of the entire Society of Jesus). Now his ordeal was the

situation in Poland. There, he came into contact with individuals who, he wrote,

“were really quite boorish,” and who reserved “any store of love and courtesy

they possessed wholly for themselves.” But the main issue was that the local

Church had sunk into the ground. He reckoned that in Poland, just as in

Germany, there were questions to be asked regarding whether Catholicism really

still had a future there. And if so, in what form? Yet although he judged

Poland to be on the verge of religious and cultural meltdown, it was also for

this very reason just where he thought he and his brothers needed to take

action. Here, he was convinced was “a vast untilled field for the labourers of

Christ,” only awaiting cultivation. In the last letter he wrote General Lainez

from Poland on 10 February 1559, he laid great stress on this point, noting,

“However much more afflicted and even hopeless things are in the judgment of

the world, how much more will it be ours to carry strength to the hopeless

because we are of the Company of Jesus.”

It was no coincidence that it was Peter Canisius who, in his letters from Poland at the end of the 1550s, reminded the Superior General that the refusal to slide into despair when facing desperate situations was something of Jesuit speciality. Instead, all hands were needed on deck “without any turning back or excuses,” as the Society’s Constitutions state, so that rays of hope, consolation and trust might shed light on these bleak scenarios. By the age of 17, Peter Canisius had already made a note in Latin in his school textbook concerning the need to persevere amid desperate circumstances. For the rest of his life, that word “persevera” would be his motto. As a young man, he had also scribbled the words “No one should ever make us despair!” under a devotional image of the Crucifixion. In 1583, when the sixty-something Canisius wrote a memorandum to the fourth Superior General, Claudio Acquaviva, one of his key counsels regarding the apostolate in Germany was “above all, guard to against the spirit of timorousness and despair.”

He knew from years of personal experience that the Jesuit presence alongside Jesuit resilience in the face of frustration were urgently required, not only in the Rome of Paul IV nor amid the turbulence of Poland, but above all in a Germany rattled by the Reformation. Canisius had become a Jesuit at the age of 22 in 1543, under the influence of that great master of the Exercises, Peter Favre. In the Autumn of 1549, after a few years in Cologne and even fewer in Italy at Messina and Rome, he had returned north, intent on saving Catholicism in the Holy Roman Empire in Germany. Many in Rome, including the Pope, believed this a waste of effort, opining that more than 25 years after the Reformation, there was nothing for the Catholic Church to do in Germany. That in fact, it had definitely missed the boat. Peter Canisius thought otherwise. He thought like a Jesuit. He saw his vocation as being in just the place where the Catholic Church in all likelihood had no future. That was the very spot where he longed to effect Catholicism’s renaissance. To that end, he founded Jesuit colleges, wrote books, and preached thousands of sermons over the course of nearly half a century. Then what no one had remotely expected transpired: in all his endeavours, he enjoyed resounding success!

In large measure, it was due to his ministry that German Catholicism had a renaissance in the 16th century. That renaissance, furthermore, had repercussions far beyond the German borders. Canisius’s refusal to despair over the Church’s desperate situation sparked a genuine change of direction. In 1640, the Jesuits published a large and splendid tome to mark the centenary of their foundation. In this, they remarked of Canisius: “To no one as much as him does the Society of Jesus and Catholicism in Germany owe so much.”

How right they were!