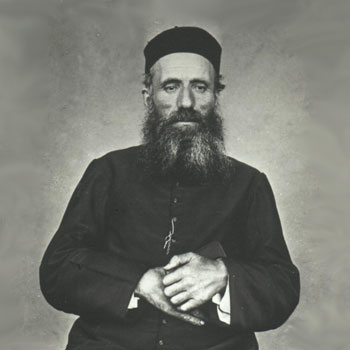

Jacques Berthieu

Saint

- Death: 06/08/1896

- Nationality (place of birth): France

Fr. Jacques Berthieu, a French Jesuit (1838-1896), priest and missionary in Madagascar, was declared a blessed martyr of faith and chastity by Pope Paul VI in 1965 during the Second Vatican Council. He will be canonized in Rome on October 21st with six other Blessed. This day coincides with the World Mission Sunday and is part of the celebration of the Year of Faith and the Synod of Bishops on the New Evangelization. Moreover, for the Society of Jesus, this year 2012 is also marked by the Congregation of Procurators which took place last July in Nairobi. The apostolic vitality of the provinces of Africa and Madagascar (that are part of JESAM) and our renewed awareness of sentire cum Ecclesia invite us to receive with fervor the witness of Jacques Berthieu. After recalling the stages of his life and his martyrdom according to the sources, I will highlight some aspects of his holiness that challenge us today.

Jacques Berthieu was born on 27 November 1838, in the area of Montlogis, in Polminhac, in the Auvergne in central France where his parents were farmers. He studied at the seminary of Saint-Four and was ordained to the priesthood for this diocese in 1864. He was appointed vicar in Roannes-Saint-Mary, where he remained for nine years. Because of his desire to evangelize distant lands, and to ground his spiritual life in the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, he sought admission to the Society of Jesus and entered the novitiate in Pau in 1873. He sailed from the port of Marseille in 1875 to two islands in the vicinity of Madagascar: Réunion and Sainte-Marie (at that time dependent on France and today called Nosy Bohara) where he studied Malagasy and prepared himself for the mission.

In 1881, French legislation closed French territories to Jesuits, a measure which compelled Jacques Berthieu to relocate to the large island of Madagascar. He first worked in the district of Ambohimandroso-Ambalavao, in Fianarantsoa, the southern part of the highlands. During the first Franco–Malagasy war, he carried out various ministries on the eastern and northern coastlines. From 1886 on, he supervised the mission of Ambositra, 250 km South of Antananarivo, and later, the mission of Anjozorofady-Ambatomainty, north of the capital. A second war forced him to move further. In 1895, the Menalamba (“red shawl”) revolt targeted Christians as well as the colonizers. Jacques Berthieu sought to place the Christians under the protection of French troops. Deprived of this protection by a French colonel whom Berthieu had chastised for his behavior with the women of the country, Berthieu led a convoy of Christians towards Antananarivo and stopped in the village of Ambohibemasoandro. On 8 June 1896, the Menalamba entered the village, and finally found Jacques Berthieu who had been hiding in the house of a Protestant friend. They seized him and stripped him of his cassock. One of them snatched his crucifix from him, saying: “Is this your amulet? Is it thus that you mislead the people? Will you continue to pray for a long time?” He responded: “I have to pray until I die.” One of them then struck Berthieu’s forehead with a machete; Berthieu fell to his knees, bleeding profusely. The Menalamba then led him away for what would be a long trek. Because of his wound, Jacques Berthieu said to those who were leading him: “Let go of my hands so that I can take my handkerchief from my pocket to clean the blood from my eyes, because I can no longer see the way.” Along the way, when someone approached him, Jacques Berthieu asked him: “Have you received baptism, my son?” “No,” answered the other. Searching his pocket, Jacques Berthieu drew out a cross and two medals and gave them to him, saying: “Pray to Jesus Christ all the days of your life. We will no longer see each other, but do not forget this day. Learn the Christian religion and ask for baptism when you see a priest.”

After about a ten kilometer march, they reached the village of Ambohitra where the church Berthieu had built was located. Someone insisted that it would not be possible for Berthieu to enter the camp because he would desecrate the “sacred objects” (referring to the fetishes). Three times, they threw a stone at him, and the third time Berthieu fell prostrate. Not far from the village, since Berthieu was sweating, a Menalamba took Berthieu’s handkerchief, soaked it in mud and dirty water, and tied it around Berthieu’s head, as they jeered at him, shouting: “Behold the king of the Vazaha (Europeans)”. Some then went on to emasculate him, which resulted in a fresh loss of blood that exhausted him.

As night drew near, in Ambiatibe, a village 50 kilometers north of Antananarivo, after some deliberation, a decision was made to kill Berthieu. The chief gathered a platoon of six men armed with guns. At the sight, Jacques Berthieu knelt down. Two men fired simultaneously at him, but missed. Berthieu made the sign of the cross and bowed his head. One of the chiefs approached him and said: “Give up your hateful religion, do not mislead the people anymore, and we will make you our counselor and our chief, and we will spare you.” He replied: “I cannot consent to this; I prefer to die.” Two men fired again. Berthieu bowed his head in prayer once more, and they missed him. Another fired a fifth shot, which hit Berthieu without killing him. He remained on his knees. A last shot, fired at close range, finally killed Jacques Berthieu.

As a missionary, Jacques Berthieu described his task thus: “This is what it means to be a missionary: to make oneself all things to all people, both interiorly and externally; to be responsible for everything, people, animals, and things, and all this in order to gain souls, with a large and generous heart.” His many efforts to promote education, to construct buildings, irrigation and gardens, and to develop agricultural training all give witness to these words. He was a tireless catechist. A young school teacher, who was accompanying him on a journey, noticed that even while on horseback, Berthieu still had his catechism open before him. The teacher asked him: “Father, why are you still studying the catechism?” He answered: “My son, the catechism is a book one can never understand deeply enough, since it contains all of Catholic doctrine.” In those days, once on foreign mission, there was no question of returning to one’s country of origin. “God knows,” Berthieu said, “how much I still love the soil of my country and the beloved land of the Auvergne. And yet God has given me the grace to love even more these uncultivated fields of Madagascar, where I can only catch a few souls for our Lord… The mission progresses, even though the fruit is still a matter of hope in some places, and hardly visible in others. But what does it matter, so long as we are good sowers? God will give growth when the time comes.”

A man of prayer, Jacques Berthieu drew his strength from it. “Whenever I looked for him,” declared one of the catechists, “I found him almost always on his knees in his room.” Another said: “I have seen no other Father remain so long before the Blessed Sacrament. Whenever we looked for him, we were sure to find him there.” A brother of his community also gave this testimony: “While he was convalescing, each time I entered his room, I found him on his knees, praying.” His love for God was such that they called him “tia vavaka” (the pious one). He was always seen with the rosary or the breviary in his hands. His faith expressed itself in his devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, the Eucharist being the source of his spiritual life. He also professed a special devotion to the Sacred Heart to which he consecrated himself in Paray-le-Monial before departing for mission, and he became the apostle of this devotion among the Malagasy Christians. A fervent devotee of the Virgin Mary, he went on pilgrimage to Lourdes, and the rosary was his favorite prayer; it was this prayer that he recited while he was being led to his death. He also venerated Saint Joseph.

As a pastor, he addressed Christians with the very words of Christ: “my little children” (Jn 13, 33); as for his executioners, he questioned them with gentleness: “ry zanako, my children.” His charity was full of respect for others, even when he had to correct an erring believer. And yet, he knew how to speak strongly and firmly whenever he judged that the interests of God and of the Church were at stake. He did not hide the demands of Christian life, beginning with the unity and the indissolubility of monogamous marriage. Polygamy being the usual practice at the time, he denounced the injustice and the abuses it generated, thus creating enemies, especially among the powerful.

On the eve of his death, while he was heading towards the capital with the Christians hunted down by the Menalamba, he was moved with compassion at the sight of a young man with a wounded foot. Berthieu began looking for carriers, offering a large amount of money for this service, but all refused. Descending from his horse, Berthieu lifted the disabled man onto his mount, and despite Berthieu’s own weakness, he himself continued the journey on foot, while pulling the animal by the bridle. “He was gentle,” declared a witness, “patient, zealous in carrying out his ministry whenever he was called, even when someone called him at midnight or when it was raining heavily.” In the south of Anjozorofady lived two female lepers. Whenever he returned from his travels, he would visit them, bring them food and clothes, and teach them catechism, until he baptized them. He considered the accompaniment of the dying in their agony a most important ministry: “Whether I am eating or sleeping,” he would say, “do not be ashamed to call me; for me there is no stricter obligation than to visit the dying.”

The total and irreversible gift of his life in the following of Christ was at the heart of his commitment. In the midst of trials, he retained his sense of humor, and remained affable, humble and helpful. He liked to quote the Gospel passage: “Do not be afraid of those who kill the body, but rather of those who make one lose one’s soul.” (cf. Mt 10:28). In his instructions, he often spoke of the resurrection of the dead. The faithful remembered the following sentence: “Even if you are eaten by a crocodile, you will rise again.” Was this a premonition of his own end? In fact, after his death, two inhabitants of Ambiatibe dragged his body to the river Mananara, a short distance away from the place of his martyrdom, and his remains disappeared.

The Society rejoices that the Church canonizes a new saint from among us, proposes him as a model to all the faithful, and invites them to seek his intercession. Certainly the historical context and the modalities of mission have changed from the end of the 19th century to our time; it is the role of historians to investigate more closely what actually happened and of hagiographers to identify the most significant aspects of holiness.

May the Holy Spirit help us put into practice the choices of Jacques Berthieu: his passion for a challenging mission that led him to another country, another language, and another culture; his personal attachment to the Lord expressed in prayer; his pastoral zeal, which was simultaneously a fraternal love of the faithful entrusted to his care, and a commitment to lead them higher on the Christian way; and finally, a life lived as gift, a choice lived out every day until the death which definitively configured him to Christ.

May the intercession of Jacques Berthieu help us to recognize the strength that is given to us in our weakness, so that we might be live our vocation with fidelity and joy, and give ourselves totally to the mission received from the Lord!

Fraternally yours in the Lord,

Adolfo Nicolás, S.I.Superior General

Rome, 15 October 2012